The geological time scale is a reference system that classifies different strata (rock layers) of earth on the basis of the time during which they bestrode the land. The timescale is divided into aeons which are further subdivided into eras, periods and finally epochs. Now, an epoch is the time during which a series (or simply rock layers) is deposited. We currently live in the Holocene epoch– of the Quartenary period– which began around 11,700 years ago (approx. 9700 BCE). The humans who thrived during this period are generally referred to as ‘modern’ humans / homo sapiens. The other members of the Homo species namely Homo Habilis, Homo erectus, Homo Neanderthalensis — our closest evolutionary cousins — went extinct by then.

300,000 years back, modern humans began emerging in Africa. Roughly 70,000 years ago, their first ‘successful’ Out of Africa (OoA) migration took place; thus being entitled as the ancestors of today’s non-African population. 5000 years later, they reached India and thereafter leaving generations behind who would later mix with zagrosian agriculturists who had migrated from Iran. Together, they give birth to one of the most advanced civilisations of its age which took root by the basins of the Indus River — the Indus Valley Civilization (also called Harappan civilisation). The monsoon river Ghaggar-Hakra too fed the settlements.

Category: Uncategorized

-

#ai1 – IH – Birth of a Civilisation

-

How Islam came to India

Islam came to India through a number of channels. To confine the onset of this religion in the subcontinent to merely invasions has become a habitual testimony yet the truth speaks otherwise.

Giving a brief summary below of some of these “channels”

First, as is expected, through invasions. Set off in the 8th century in Sind by Arabs. Next on the line are the Turks and Afghans, both of whom invaded the North-west in the 11th century and dominated northern India. Lastly, the Mughals in the 16th century.Secondly, commerce. Afghan and Turkish traders conducted transactions in Northern India and settled there.

That covers only the northern parts. What about other regions, especially the south west which has a significant Muslim population and a distinct culture of its own?

People hailing from Arabia and East Africa traded with those residing in the western coastline from as early as 8th century and eventually settled there by 9th century.1

These intercultural alliances birthed the various religious groups of Islam, particular to its own geography, such as the Bohras, Khojas, Navayaths and Mapillas.

Third, army recruitments. Mercenaries from the central Asia and especially East Africa, incidentally regions with a significant Muslim population, were recruited in the armies of Indian kings. Likewise, soldiers from India too were recruited to fight for Afghan and Turkish kings; a pertinent example being that of Mahmud of Ghazni, who had a Hindu general in his army named Tilak. Mahmud’s empire spanned as wide as to include Kashmir and Punjab.

Now fourth, Sufis. The Sufis, most of whom hailed from central Asia and some from Persia, carried out religious missions in the subcontinent. Most held an eclectic outlook and were seldom orthodox, borrowing and interspersing with the local religions and traditions, and subsequently flowering into a syncretic form of Islam.

An attempt has been made here to only recount the salient ways in which Islam reached the subcontinent. Indubitably, there ought to be other sources too, which has been omitted here with due regard to maintaining the brevity of the piece.

Notes

- Trade was not an anomaly; as per records, Kerala is said to have had good trade relations with Rome as well during the zenith of the latter’s empire; all of which was made possible because of maritime trade via Arabian sea. Kerala is the state that has the longest coastline, the tidal waves billowing its rocky banks.

-

Manchester of India

Manchester is a city situated in north west England, to the south of which lies river Mersey. Infamous for being at the forefront of the Industrial Revolution and consequently the first industrialised city in the world, Manchester was the hub for textile manufacturing, particularly cotton. This is also the reason why the city had been often dubbed “cottonopolis”.

The city of Manchester is not without parallels, at least not in India. Sitting at the banks of the Sabarmati river, which lines through the state of Gujarat in North-west India is Ahmedabad. This city, the biggest in Gujarat is the hub of cotton textile industry in India. Moreover, the waters of Sabarmati have proven to be a boon for the thriving cotton warehouses in that it helps dye cotton threads. The semi-arid climate of the city too makes for everything necessary for the industries to flourish. The cotton manufactured herein are exported to the rest of the world, much akin to Manchester of England.

For these reasons, Ahmedabad is fittingly called the ‘Manchester of India’. -

Mahatma

‘Mahatma’ is a Sanskrit word which literally means ‘Great Soul’. Gandhi was so entitled by the Nobel prize-winning poet Rabindranath Tagore in 1915.

It must be said that this was indeed a befitting accreditation for Gandhi; for those terse and thoughtful words, and noble and unpretentious endeavours, couldn’t have sprung from a greater soul than his.

Yet, he never basked in the honour of being bestowed with such a title. Many a times, he relinquished it for he believed that he was not deserving of a title so noble. Here are a few excerpts from his writings which illustrate this point.

The only virtue I claim is truth and non-violence. I lay no claim to superhuman powers. I want none. I wear the same corruptible flesh that the weakest of my fellow beings wear and am liable to err as any. My services have many limitations, but God has up to now blessed them in spite of imperfections.

The mahatma I leave to his fate. Though a non-co-operator I shall gladly subscribe to a bill to make it criminal for anybody to call me a mahatma and to touch my feet. Where I can impose the law myself, at the ashram, the practice is criminal.

-

IH – The Beginnings

A brief of India’s physical features

A tangerine-hued semi-molten core, jacketed by a mantle and a crust. The smudged image that forms in one’s mind when asked of the cross-section of earth. Indeed, it’s a retreat to sixth grade geography lessons but nevertheless insignificant. For as we embark on this seemingly pallid journey gliding by the contours of the Indian subcontinent’s less-than-mundane past, it beckons that we run our eyes over the genesis of this landmass.

Now, coming back to the point. Owing to currents that emanate from the aforesaid core, the crust fractures into plates which jostle against each other; in precise terms the geological process named tectonic shift.

As one whole, the plates are called Pangea which consists of two parts– the Laurasia and Gondwanaland, India being a scrap of the latter. She slid north-eastwards through the Tethys sea, to finally lunge beneath the Eurasian plate, the push leading to the bulge of the Himalayas, ‘the youngest, largest and highest mountain range on earth.’ Note that these tenacious movements spanned millions of years.

The Himalayas, running along the northern periphery is home to the highest fourteen peaks in the world, the most prominent one among them being the Mt. Everest (roughly 8.8 km). Parallel to the Great Himalayas are its less taller counterparts, the Middle Himalayas and Outer Himalayas. In the north-west we encounter troughs in the mountainscape, which marks the many passages to India – the Khyber Pass , the Bolan pass and the Gomal Pass.

Though writers contest that the Himalayas bear a significant influence in the subcontinent, in all its sententious aspects, Basham opines that the point has been a tad too much overstated. No more than shaping the climate of the region should she be accredited for. That the Himalayas gave India an advantageous seclusion may seem geographically and even politically appealing yet the truth lies in that these ranges were cut through by travellers, traders and settlers of different sorts for many years. The guard hasn’t always been up.

The precipitate of the moisture-laden clouds that drifts over and the melting snow of the Himalayas birthed the rivers Indus, Ganga and Brahmaputra, rolling down to its foot and forth, sedimenting a broad strip of alluvium that would become one of the most fertile regions in the world, the Indo-Gangetic plain. Naturally, it was here that humans and their aspirations blossomed.

The Indus springs in the Tibet near the Manasarovar lake, traverses along the north-west and sheds into the Arabian sea. The Ganga, alongside Yamuna, both of which rises from Himalayan glaciers (Gaumukh and Yamunotri respectively) wade together to finally wed at Allahabad and join its mate, the Brahmaputra, before gushing into the prodigious Bay of Bengal.

Nestled between the Indus and the Northern plains is the Aravalli hills and to its left, the Thar desert.

-

“Crave not the pleasures of Paradise,” says Kabir

Paradise. That symphonic destination humans have hankered for centuries. It makes them philanthropes. It makes them holier-than-thou.

It makes them sympathize the penurious, save the callous dough thrust at their warped ashet, inedible perhaps.

It makes them plonk that extra penny into the crevice of the gold-rimmed temple coffer; which sits before the deity, destined for the priest, brimming of course.

It turns them into devout sycophants.

As for the obtuse casuists, some remain in their nutshells while some, in the garb of religion, become extremists.

To descend on Swarg Loka, tarry in its bountiful pleasures until next birth or; to reach the garden of Jannah, the “gardens of pleasure”—the prospects of which deliquesces many to the realms of piety— appears to be the ultimate pursuit of almost all, barring the atheists. This heavenly pursuit makes the world a better place alleges the blind optimist : “It turns them into Good Samaritans!”

As the frothy waves gush through the meanders, so does it bring along the dross, the debris, the incongruous rocks; just like the offcuts of many good deeds in this world. No endeavor is ever so pristine in its motives. In the course of one’s journey towards the end, top or bottom, the naives are sometimes impelled from within to despise what doesn’t conform to their canons; this robbing them of all virtue that was left, if any.

The rationale behind this dystopian prolixity? It brings me to a 15th century poet who catechized the proponents of these ideas, succinctly razing all that was held banal. Kabir.

It would be an injustice to merely regard him as a Bhakti poet, just like anybody else who would have traversed similar terrains during those times. For poetry aside, he is deserving of titles like philosopher ,social commentator and satirist. Through his often inconspicuous and riddling rhetoric, adorned with the usage of upside-down language, Kabir exposes the sanctimonious attitudes of ardent religionists and their unfounded beliefs and rituals. A believer of ‘personal god’, he considered himself as ‘the child of Allah and Ram”.

In many of his verses, he disparagingly talks of Hinduism and Islam, their hollow obsessions and esoteric compositions. For instance, he passed snide remarks about Hindus’ and Muslims’ animal sacrificial rituals:

‘One slaughters goats, one slaughters cows, they squander their birth in isms’.

If we are to wade through Kabir’s poems denouncing Hindu and Islamic beliefs in detail, a mere assortment of words would not suffice. That is a topic of contention for another day. If we cloister it to a passage, I’m afraid it would take the form of a panegyric, unintentionally deluding the nuances of it.

Let’s go!

Everyone keeps saying,

As if they knew where paradise is,

But ask them what lies beyond

The street they live on,

They’ll give you a blank look.

If paradise is where they’re heading,

Paradise is not where they’ll end up.

And what if the talk of paradise is just hearsay?

You better check out the place yourself.

As for me, says Kabir, if you’re listening,

Good company’s all I seek.1

The aforementioned is one among Kabir’s works which blatantly reveals his disapproval of the whole purported idea of paradise. It’s also a mockery of society. It underscores their credulity and inability to mull over any idea in depth.

In another set of verses, he deploys the allegory of a ferry that would apparently take him (and his peers perhaps), to their desired destination. In these lines, he inquires, in the guise of a ridicule, ‘Is there a paradise anyway?’

I’m waiting for the ferry,

But where are we going,

And is there a paradise anyway?

Besides,

What will I,

Who see you everywhere,

Do there?

I’m okay where I am, says Kabir.

Spare me the trip.2

Hell and heaven did not qualify as a dichotomy for Kabir as he was indifferent to both. In nâ main dharmî nahîn adharm3 he says,

I am neither pious nor ungodly, I live neither by law nor by

sense,

I am neither a speaker nor hearer, I am neither a servant nor

master, I am neither bond nor free,

I am neither detached nor attached.

I am far from none: I am near to none.

I shall go neither to hell nor to heaven.

I do all works; yet I am apart from all works.

Few comprehend my meaning: he who can comprehend it, he sits

unmoved.

Kabîr seeks neither to establish nor to destroy.

Taking a dig at the unlettered and gullible, in another clever usage of satire, he pillories his dear pandits.

Pandit, do some research

and let me know

how to destroy transiency.

Money, religion, pleasure, salvation—

which way do they stay, brother?

North, South, East or West?

In heaven or the underworld?

If Gopal is everywhere, where is the hell?

Heaven and hell are for the ignorant,

not for those who know Hari.

The fearful thing that everyone fears,

I don’t fear.

I’m not confused about sin and purity,

heaven and hell.

Kabir says, seekers, listen:

Wherever you are

is the entry point.

These lines are suffused with his intrepidity and clarity of thought. He is seldom ambiguous. He speaks his mind, and that too, to those worthy of such admonishments.

Lastly,

‘O Qazi, nothing is accomplished by mere talk

By fasting, passing the time with prayers and the creed will not achieve paradise;

He who knows how can view the Ka’ba in his own body’

As is evident, Kabir is jeering at the Qazi4, scoffing at his rendition of prayers five times a day and the month-long fasts he undertakes every year.

Eulogies aside, one has to be cautious while credulously taking Kabir’s words as gospel since much of what we deem to have hailed from Kabir may not be his after all. Owing to the unavailability of authentic manuscripts that dates back to his period, credibility of the lines attributed to him remains elusive. Nevertheless, his verses were passed onto each generation orally and scholars devoted to his works have extracted these and compiled them with astonishing dexterity.

Today, some of Kabir’s verses remain inscribed on tattered pages of textbooks, soon to be erased from the minds of indolent highschoolers, thanks to the conundrum of impotent ideas she’s fed thereafter. Perhaps, considering the erratic times we live in, we need to hark back to these verses once in a while. One, so as to take refuge from the cloister of insanity we’ve been trapped in and two, more importantly, to forbid our gullible natures from being preyed on by the corrupt.

Moreover, injustice and intolerance pervading our times have forced us to rethink and scrutinize our own actions; actions to please somebody, some unknown.

For all we know, as Kabir put it,

‘What if the talk of paradise is just hearsay?’ And, ‘Is there a paradise anyway?’

Notes

[1] K., Mehrotra, A. K., & Doniger, W. (2011). Songs of Kabir. Adfo Books.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Retrieved from SONGS OF KABÎR – Translated by Rabindranath Tagore

Full text available here.

[4] Qazi is a Muslim judge who delivers decisions in accordance with the Shariah Law.

More

A notable work worth mentioning :

The Bijak of Kabir by Linda Hess

-

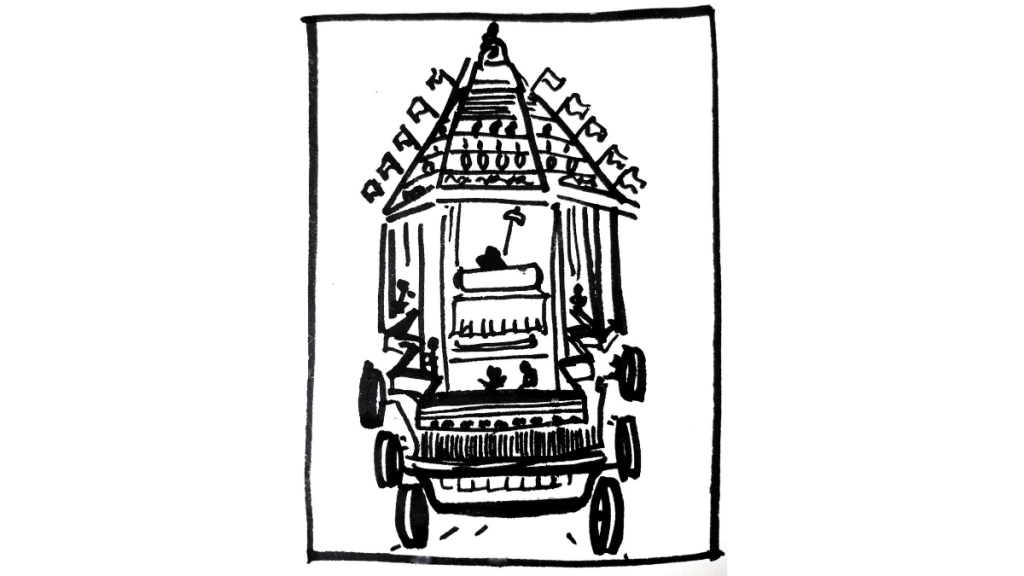

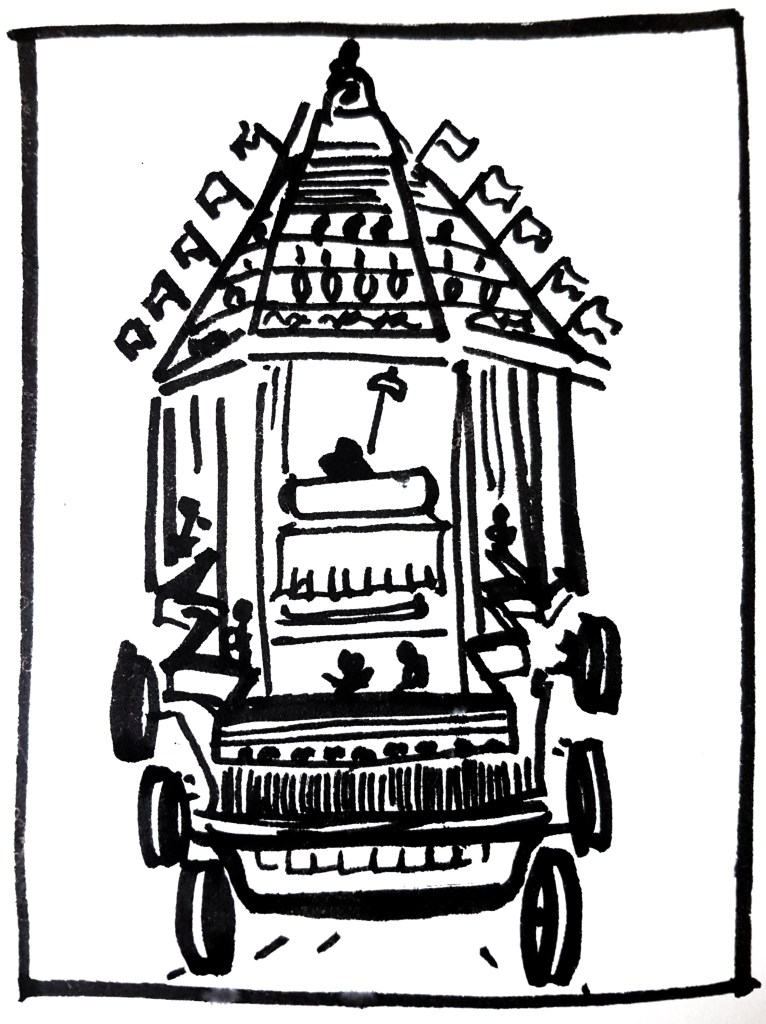

Tracing the ‘Juggernaut’

It was early 14th century, and in Puri, abutted on the eastern coast of Orissa, the day that recurred once every year had finally arrived; Rath Yatra. A giant idol studded and throned on gold, venerated by the whole of subcontinent, was stowed on a huge, ornamented chariot and the royals, pilgrims and the commons would cruise it together with much pomp and music. The maidens would go to the fore and chant in a “marvelous manner”, one traveller recorded. What ensued thereafter would be the ritual that would bewitch and horrify other unacquainted onlookers to an equal measure. The assembled pious pilgrims casted their bodies underneath the destructive wheels of the chariot in the belief that they, the devout mortals, be sacrificed to Lord Vishnu, the Jagganath. And hence, they perished, or in accordance with customary beliefs, went to glory.

One who had witnessed the procession to the hilt was the Franciscan missionary, Friar Odoric, the aforesaid traveller. He produced an account of the incident in his journal and thus this tale, perhaps exaggerated, became rapidly popular through the hallways of Europe. In the 19th century especially, the English, much captivated by the tale, would anglicize it and give birth to the word—‘juggernaut’. Thereupon, ‘Juggernaut’ was literally used to refer to anything that had the calamitous capability of fiercely destructing or crushing all that comes to its path.

For those seeking the meaning of ‘Jagganath’ :

‘Jagannath’, which literally means ‘Lord of the Universe’ has its roots in Sanskrit. In Sanskrit, जगन्नाथ can be deconstructed to ‘Jagat’ which means ‘universe’ and ’natha’ which means ‘lord’ or ‘master’.This of course, is not the only story that pervades the conception of the word ‘juggernaut’. Another source traces its origin from the details inhabiting the letters mailed home by an Anglican chaplain, Rev. Claudius Buchanan from India. This took place during the early 19th century. Expectedly, he was repelled by the grotesque ritual and wrote back home vilifying it as a virulent cult. Having been discipled in missionary education, he held strong ecclesiastical views which tempted him to see the ‘other’ as a ghoulish religion people blindly embraced. Through his eyes, the seemingly dissonant state of religions in India required the intervention of Christian missions. In an attempt to apprise his Christian readers, for a piece published in Christian Researches of Asia in 1811, he drew parallels between the ritual he witnessed in India with the practice of sacrificing children to the heathen god Moloch.

The description, which became popular amongst the anglophone audience, was this:

“The idol called Juggernaut has been considered as the Moloch of the present age; and he is justly so named, for the sacrifices offered up to him by self-devotement are not less criminal, perhaps not less numerous, than those recorded of the Moloch of Cannan.”

Buchanan even went to the extent of glossing upon an unfounded proposition that even the most unlettered Indian would find unpalatable today; that the Jagganath (or Juggernaut) “is said to smile when the libation of blood is made.” Likewise, a missionary magazine in 1813, corrupting the supposedly dangerous aura that flavors the idea of a juggernaut, likened the latter to the perceived evils of consuming alcohol.

Decades later, though the word ‘juggernaut’ was reinstated to its forbearers, the concocted meaning of the word assumed permanence. This word has since made its appearance across different genres, places, and times. ‘Juggernaut’, a villainous character described to be habitually at loggerheads with other heroes, made its way into Marvel Comics in 1965. An anti-communist communist book published in 1932 was named ‘The Red Juggernaut’. The word also makes an ephemeral appearance in Charlotte Bronte’s ‘Jane Eyre’.

The excerpt:

“This girl, this child, the native of a Christian land, worse than many a little heathen who says its prayers to Brahma and kneels before Juggernaut—this girl is—a liar!”

Apart from the few aforementioned, numerous examples prevail.

Surpassing countless delusions, suppositions, imaginations, is how the mighty word of juggernaut has come to resemble the omnipotent—literal or metaphorical— force that is ascribed to it today. Although we do not know whether this journey of conflicting interpretations shall continue, or even if—giving credence to an optimistic hunch—it reaches where it belonged once, one can be sure that this word would burgeon, attributing to it more things deemed unrelenting, for no other word commands such puissant vigor as the ‘juggernaut’.

More

The travels of Friar Odoric was later included in the travels of Sir John Mandeville, from which we reconstruct much of the information that we know about the origin of this word today. Interested readers, who would like to read about other first-hand accounts that Odoric produced from his observations, can refer to the text here.

-

‘Mary Ventura and the Ninth Kingdom’ by Sylvia Plath

A rejected short story, written during the days succeeding her home departure, while in college, and even dismissed by its own writer as a “vague symbolic tale”, Mary Ventura and the Ninth Kingdom is an absorbing story running almost fifty pages that rightly possesses nuances of mystery, death, sexuality with a tinge of juvenility. Not being one of her finest works, it is unsurprising that this piece was turned down by Mademoiselle magazine on submission. Perhaps, this unpublished work of the twenty-year-old Plath was fated to wither in her archives for years until the academic Judith Glazer-Raymo unearthed them.

The basic thread of the story runs through Mary Ventura, the protagonist, who wades through unwieldy circumstances on a train ride—a ride destined for the “ninth kingdom”, the abode of frozen will, one where you’re coaxed to stomach and surrender to fate, and purportedly, as the overtones of the story suggests, to meet one’s makers. Enriching the narrative’s platter are Plath’s colored descriptions of the scenes that encompass the story, often disturbing that it compels one to foresee the slowly unfolding doom. To quote a few lines:

“Blood oozed from a purpling bruise. The younger boy began to whimper.”

“The train had shot into the somber gray afternoon, and the bleak autumn fields stretched away on either side of the tracks beyond the cinder beds. In the sky hung a flat orange disc that was the sun.”

In a notable conversation with the woman Mary encountered in the train, the reader, who can prudently parse the context, would be much able to suppose a faint suspense that builds in the novel thereafter.

[Mary] “I shouldn’t wonder. It is a comfortable ride, really. They do so many nice extra little things, like the refreshments every hour, and the drinks in the card room, and the lounges in the dining car. It’s almost as good as a hotel.”

The woman flashed her a sharp look.

“Yes my dear,” she said dryly, “but remember you pay for it. You pay for it all in the end. It’s their business to make the trip attractive. The train company has more than a pure friendly interest in the passengers.”

And then the story proceeds spanning Mary’s entire journey, and the sometimes fortuitous exchanges and situations that ultimately make Mary refurbish the dole that confronts her life.

Though not an outright masterpiece, the contours of this story reflects Plath’s dubiety about the path she trods in her own life and in many instances, through Mary’s desperate enquiries and yearnings to get out, one can sense Plath’s own trepidations about her journey in this world.

Mary Ventura and the Ninth Kingdom qualifies a one-time read; however, better would be an audio version of the same, some with excellent narration accompanying it. Be not prepared to be enthralled by the tale, but grasp the vexations of a young mind that imprint the journey towards the making of a great writer.

More

-

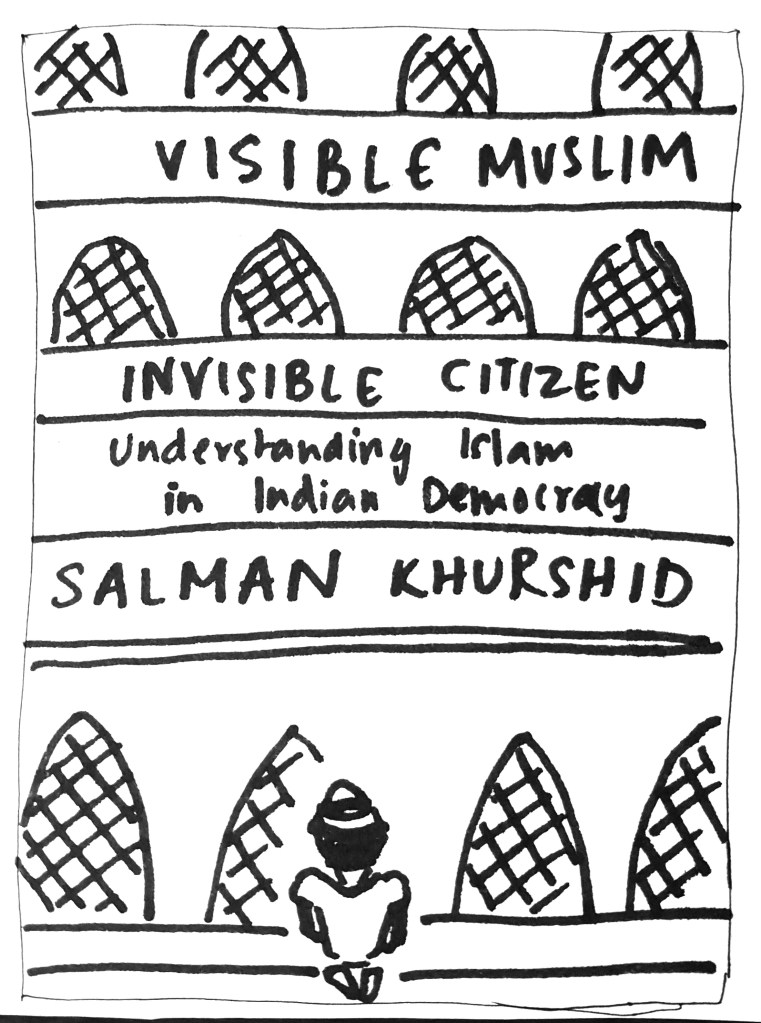

Review of Salman Khurshid’s ‘Visible Muslim, Invisible Citizen’

‘The Visible Muslim, Invisible Citizen’ is a book that proposes to understand the various tenets of Islam in the Indian Democracy. In his book, Khurshid attempts to analyse and provide a discourse on the question that is pertinent to every Indian Muslim, “What am I as a muslim?”

With the book centring on a span of topics that would be of interest to the inquisitive mind like ‘Aligarh Character Assassination’ to ‘Sufi Traditions’ , one only wishes that the author had written more on it rather than confining them briefly to a few pages. The author, professing his excellency in writing, leaves readers like myself for instance, yearning for more after each chapter.

The book begins with the description of India as a collection of multiple nationalities, the important roles that Muslims played throughout India’s struggle for independence, its history and hence proceeding onto the sensitive topic of partition. In one of the later chapters, the author notes with utmost optimism that if the reunification of Vietnam, Germany, end of apartheid in South Africa et al, had been possible, then the prospect of India and Pakistan dwelling in peace is not only achievable but also imperative for humankind. As for the involvement of Indian Muslims in the freedom struggle, Khurshid quotes the prominent writer Khushwant Singh saying, “Indian freedom is written on Muslims’ blood, their participation in [the] freedom struggle was much more in proportion to their small percentage of population.” This is indeed true, as the book chronicles the vast achievements of Indian Muslims, their persistent effort in diminishing the imperial rule and denouncing the jeopardising framework laid down my the colonials. A stirring account of the emergence of the Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) in the chapter ‘Aligarh Character Assassination’ gives one all right to believe in the extraordinary achievements of Muslims in the field of education and Sir Syed Ahmed Khan’s desire of setting up an ‘Oxbridge in the East,’ from whom the very idea of AMU was born. Further moving on, the book gives an understanding of the much debated Enemy Property Act, its implications with authentic statistics and and also, as uncanny as it may sound, a vague and condensed view on the curious case of ‘Love-Jihad’. A reader would certainly find the portion lacking in precision as the author tends to make an ambiguous judgement with regard to the issue.

In one of the later chapters, the author notes with utmost optimism that if the reunification of Vietnam, Germany, end of apartheid in South Africa et al, had been possible, then the prospect of India and Pakistan dwelling in peace is not only achievable but also imperative for humankind.

Khurshid also attempts to give an elaborate view on the contentious ‘Triple Talaq’ alluding to its ‘inherent odious nature’ and ‘questionable pedigree’. The current hotly debated case of ‘Babri Masjid’ finds its way into the book with the author producing an excellent account of its compelling history, which every Indian must know, and the different claims that has been laid down by various groups over the years regarding the actual proprietor of the land. Since Babur, the founder of the Mughal Dynasty, has been the prime target of many these days, for having invaded India and ruled, the author says, ‘The fact is quite the opposite, if we recall the poignant way in which Babur gave up his life for Humayun and his relationship with India, even if he did hope to return to his native land Kabul and be buried there’. A wealth of other riveting narratives appears in this book such as the history of Islam, Sufi traditions, matters of belief and faith and the lamented discontinuance of the Sachar Committee, a committee institutionalised for the report sought by the 2005 Dr. Manmohan Singh government on the contemporary status of Muslims in India.

However, despite the ignorable inadequacies of the book, one would not disagree that the author’s brilliant take on the authoritativeness of Fatwas and Muftis is the icing on the cake.

Although the apposite titling of the book intrigues one to devour in it, it must be noted that the book only partly does justice to the title as the book remains unclear with its objectives in parts that require a preconceived consensus. Nevertheless, it must be treated as a great read as it is one-of-a-kind books out there that seeks to be explanative of the plethora of issues that affect Indian muslims today and the lesser-known facets of their fascinating history. Their achievements, efforts, hard work had blossomed into our knowledge quite infrequently and this book would definitely make its way into rectifying those.

-

Review of Benyamin’s ‘Goat Days’

“After all it is only hope that makes a man go forward”, said he who had faced the misfortunes worth suffering a thousand lives, Najeeb. In the dreary deserts, with only the sands visible to the faintest eyes, grazing the horizons and beyond, the life of any Malayali who had come to the Gulf land with far fetched dreams; their lives can only be far from fathomable. ‘Goat Days’ poses as a mirage of that harsh truth. Under the veil of luxuries and moolah of the Arabian world lies the cloaked plight of these hapless men, cajoled by the knot they’ve let themselves get entangled in, yet apprehensive of the very chance of breaking free, lest they meet a greater catastrophe on the journey back.

Beginning with the aspirations of any young married man of the 90s, proceeding onto his tryst with the austere realities of the Arab world; the anguish, pain, suffering, wrath, caress, love, death and ultimately defeatism, this poignant novel will make one contemplate the arcane insecurity of a human — the purpose of his very existence. Enduring misery in the lone planet that he believes he is in, with none to share a beautiful sight with, is one of the greatest sorrows of life, recounts Najeeb; exposing the painstaking secret dolour of our conscience yet again.

As Najeeb wades through the flood of torments that deluge upon him, his mind in the company of Allah, his dear Hakeem and the saviour in disguise of a modern-day ‘Achates’ Ibrahim — the one that would read in between the lines, throbbing each second, would be us, the fortunates. All said and done, for definite, there exists no parallel for Benyamin’s master story-telling finesse. To reproduce a real life story with words spun into like that of a coronal of flowers, devoid of adulteration —that, only a genuine writer can. Proving his point conspicuously, through the pages of his sanctified work, Benyamin gives us the promising outlook that he’d never disappoint. As I said, this tale, is a reflection of ourselves —not the adorned physicality we’ve been exhibiting around, rather, expounding the real being in us, the woes of a human.