‘Haroun and the Sea of Stories’ is a fantastical tale — a tale we wish to revel in, the tale we wish, someday, would be our own. On the way we meet a storyteller Rashid who can spurn stores out of thin air, his wife who has a beautiful voice, and his only son Haroun. Rashid is renowned for his ability to transpose people to another realm through his invective tales. Politicians often hire him to woo voters because of his ability to keep people hooked through his marvellous storytelling. It is said none but he alone can have such a grasp over listeners’ attention. But one day all goes awry as Rashid’s wife leaves him for an unpleasant neighbour who keeps asking a question that seems to have struck a chord with Rashid’s wife, “what is the point of stories that aren’t even true?”. Soon afterwards, Rashid finds himself bereaved of that magical superpower that had rendered him invulnerable for long – the power to create stories. Haroun is devastated and Rashid becomes literally speechless. Every time Rashid attempts to narrate a story to the crowd all that comes out is a croak, much to his embarrassment and disappointment. Moreover Rashid and Co., live in a ‘sad’ city, “a city so ruinously sad that it has forgotten its name.”

Wherefrom does Rashid’s magic to create stories out of nowhere emanate? The sea of stories. But Rashid’s downturn of sorts is speculated to be the result of a despotic tyrant in the ‘Land of Chup (Silence)’ Khattam-Shud who wants the sea of stories to be poisoned (quite a devilish bloke!). As the name suggests, the inhabitants of the Land of Chup glorify silence and darkness; just a streak of light would blind them.

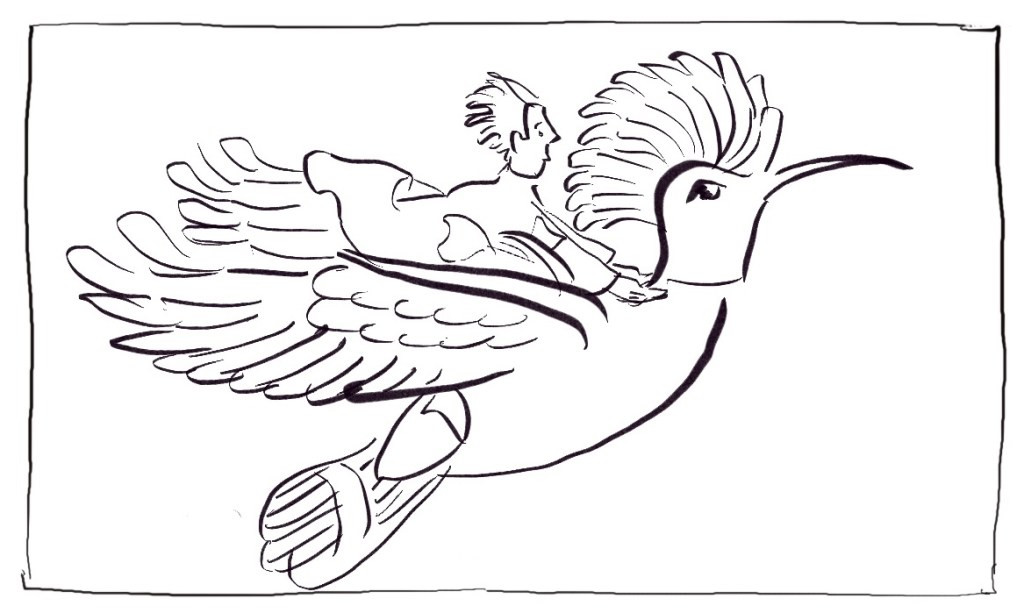

The story takes may turns hereupon; leapfrogging our way through, we find Haroun and his father at a politician’s chuckhole. During the night, when everybody’s sleeping, Haroun encounters the water genie who is responsible for the story tap through which tales metaphorically gush out enabling Rashid to tell stories. Haroun wants to cure his father’s ailment, and so he embarks on an adventure with the water genie. On the way, he meets a magical bird ‘Hoopoe’, ‘Plentimaw fishes’ and many wholesome characters. Towards the close of the mysterious journey they end up at a kingdom. To his surprise Haroun meets his father there. Fables of wisdom, betrayal, friendship, and the usual feuds, yarn along the corridors of the kingdom. In the end, Haroun manages to finish off ‘Khattam-Shud’ whose name means “completely finished” (as it ought to be). Rashid regains his voice and power of making stories. The father and the son return home, and the city in which they’ve been dwelling secures a fitting name for itself, ‘Kahani’. Miraculously, Rashid’s long-lost wife is home too.

Haroun is perhaps one of us. Just as the son of the story-teller Rashid — who finds more pleasure in pumping blahs into the ears of unsuspecting denizens than staring at his wife throughout the day — the reader too is transposed into a realm of limitless imagination. From birds that can read your mind, to princesses that sing with their unpleasant voices, ‘Haroun and the Sea of Stories’ is a complete fantasy, and a humorous one at that.

Rashid has indescribable powers for conjuring up stories out of thin air. In a land of unforgiving agony, it is stories that enliven the spirit of the townsfolk. But one day everything goes topsy-turvy. Salman Rushdie manages to transpose the gloom that impregnates the situation into one of enervating joy with an Arabian Nights-esque candour giving the reader plenty to revel in. The brilliance of Rushdie is marked by his ability to pull off this feat — of mixing a formidable threesome: magic, humour, adventure — a feat so incredible few in the literary world would be able, and willing, to emulate. To Rushdie the master storyteller here’s a fellow Haroun’s love.