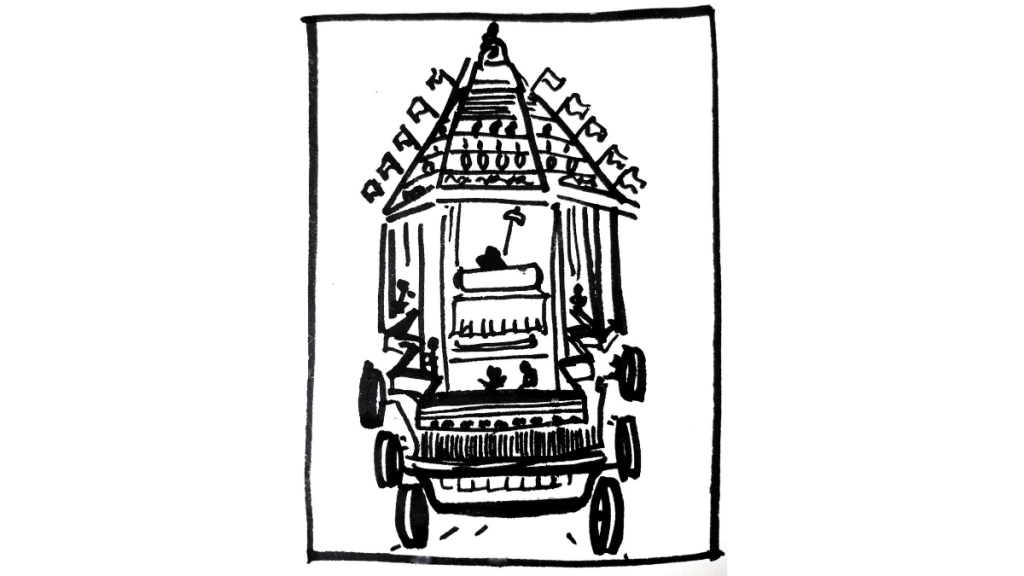

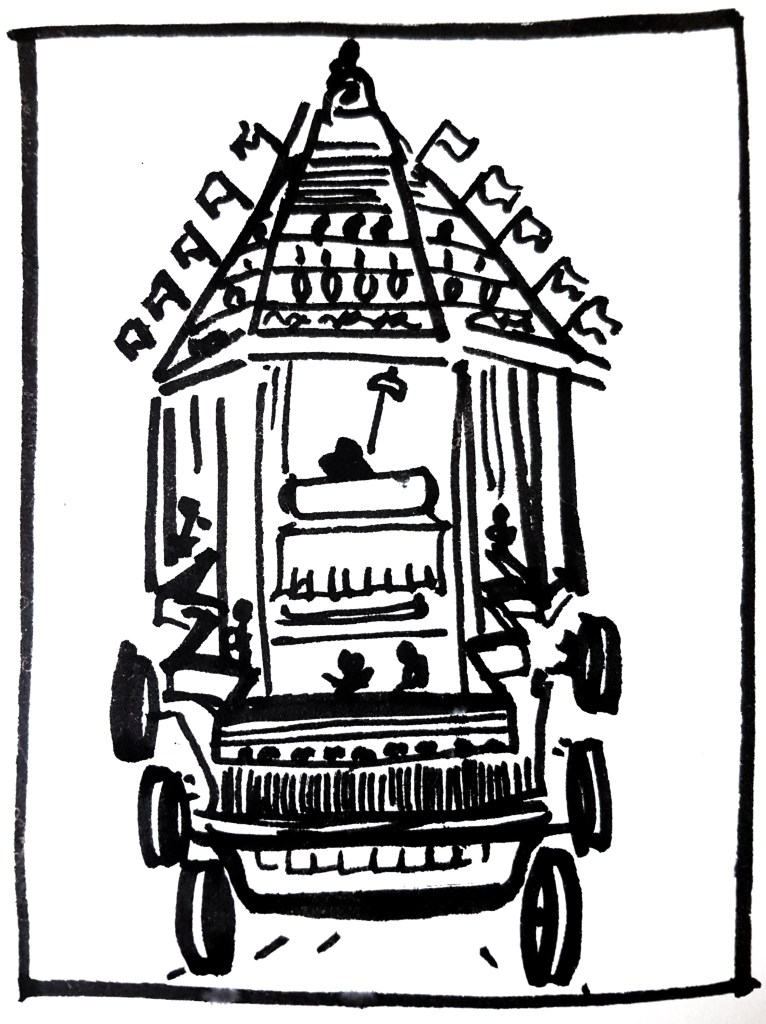

It was early 14th century, and in Puri, abutted on the eastern coast of Orissa, the day that recurred once every year had finally arrived; Rath Yatra. A giant idol studded and throned on gold, venerated by the whole of subcontinent, was stowed on a huge, ornamented chariot and the royals, pilgrims and the commons would cruise it together with much pomp and music. The maidens would go to the fore and chant in a “marvelous manner”, one traveller recorded. What ensued thereafter would be the ritual that would bewitch and horrify other unacquainted onlookers to an equal measure. The assembled pious pilgrims casted their bodies underneath the destructive wheels of the chariot in the belief that they, the devout mortals, be sacrificed to Lord Vishnu, the Jagganath. And hence, they perished, or in accordance with customary beliefs, went to glory.

One who had witnessed the procession to the hilt was the Franciscan missionary, Friar Odoric, the aforesaid traveller. He produced an account of the incident in his journal and thus this tale, perhaps exaggerated, became rapidly popular through the hallways of Europe. In the 19th century especially, the English, much captivated by the tale, would anglicize it and give birth to the word—‘juggernaut’. Thereupon, ‘Juggernaut’ was literally used to refer to anything that had the calamitous capability of fiercely destructing or crushing all that comes to its path.

For those seeking the meaning of ‘Jagganath’ :

‘Jagannath’, which literally means ‘Lord of the Universe’ has its roots in Sanskrit. In Sanskrit, जगन्नाथ can be deconstructed to ‘Jagat’ which means ‘universe’ and ’natha’ which means ‘lord’ or ‘master’.

This of course, is not the only story that pervades the conception of the word ‘juggernaut’. Another source traces its origin from the details inhabiting the letters mailed home by an Anglican chaplain, Rev. Claudius Buchanan from India. This took place during the early 19th century. Expectedly, he was repelled by the grotesque ritual and wrote back home vilifying it as a virulent cult. Having been discipled in missionary education, he held strong ecclesiastical views which tempted him to see the ‘other’ as a ghoulish religion people blindly embraced. Through his eyes, the seemingly dissonant state of religions in India required the intervention of Christian missions. In an attempt to apprise his Christian readers, for a piece published in Christian Researches of Asia in 1811, he drew parallels between the ritual he witnessed in India with the practice of sacrificing children to the heathen god Moloch.

The description, which became popular amongst the anglophone audience, was this:

“The idol called Juggernaut has been considered as the Moloch of the present age; and he is justly so named, for the sacrifices offered up to him by self-devotement are not less criminal, perhaps not less numerous, than those recorded of the Moloch of Cannan.”

Buchanan even went to the extent of glossing upon an unfounded proposition that even the most unlettered Indian would find unpalatable today; that the Jagganath (or Juggernaut) “is said to smile when the libation of blood is made.” Likewise, a missionary magazine in 1813, corrupting the supposedly dangerous aura that flavors the idea of a juggernaut, likened the latter to the perceived evils of consuming alcohol.

Decades later, though the word ‘juggernaut’ was reinstated to its forbearers, the concocted meaning of the word assumed permanence. This word has since made its appearance across different genres, places, and times. ‘Juggernaut’, a villainous character described to be habitually at loggerheads with other heroes, made its way into Marvel Comics in 1965. An anti-communist communist book published in 1932 was named ‘The Red Juggernaut’. The word also makes an ephemeral appearance in Charlotte Bronte’s ‘Jane Eyre’.

The excerpt:

“This girl, this child, the native of a Christian land, worse than many a little heathen who says its prayers to Brahma and kneels before Juggernaut—this girl is—a liar!”

Apart from the few aforementioned, numerous examples prevail.

Surpassing countless delusions, suppositions, imaginations, is how the mighty word of juggernaut has come to resemble the omnipotent—literal or metaphorical— force that is ascribed to it today. Although we do not know whether this journey of conflicting interpretations shall continue, or even if—giving credence to an optimistic hunch—it reaches where it belonged once, one can be sure that this word would burgeon, attributing to it more things deemed unrelenting, for no other word commands such puissant vigor as the ‘juggernaut’.

More

The travels of Friar Odoric was later included in the travels of Sir John Mandeville, from which we reconstruct much of the information that we know about the origin of this word today. Interested readers, who would like to read about other first-hand accounts that Odoric produced from his observations, can refer to the text here.